[ad_1]

In an era when ongoing food shortages are becoming the norm, many people are turning to gardening for the first time. However, knowing how many plants you need can be quite challenging with no prior foundation to build upon.

There’s no single right answer, and you need to consider many factors before determining what’s best for you and your family.

We’ll review several considerations and give you a few formulas to work with so you’re sure to have the best harvest possible.

Planning and Goal Setting

Like any project, adequate planning is paramount to success. Gardening is no different, and you need to do your due diligence—especially if you’ve never gardened before. Gardening often takes many years of trial and error before producing bountiful crops.

Without established objectives, your harvest is simply a matter of chance. You usually end up with too much of one vegetable and not enough of another. Proper planning will save you precious time, energy, and resources.

How Much Is Too Much?

There’s a wide pendulum from growing just enough to supplement your weekly grocery bill to growing everything you eat. Think about your available space, your level of experience, and how much time you have to spare.

Planting too much in a limited area reduces overall production because plants choke each other out when not given enough room to grow.

Additionally, food doesn’t grow itself. So make sure you have adequate time to put into whatever you plant. Watching your food rot on the vine because you don’t have time to tend to it is extremely disheartening, not to mention a complete waste of money.

How Big Is Your Family?

Obviously, the more mouths you’re trying to feed, the more plants you need. Growing for one or two people sharply contrasts with growing for four or five.

Likewise, there’s a big difference in the amount of food required for a young child versus a teenager or fully grown adult. Knowing your family and their appetites is necessary for planting the right amount.

Will You Preserve Your Harvest?

If you’re growing your own food to survive, you’ll need to preserve some of it. Gardening is hard enough by itself, but preserving what you grow is an entirely different skill set. If you intend to preserve your food, develop a solid plan for that too.

Otherwise, you’re wasting both time and money.

You can preserve food in a variety of ways:

Each method requires a unique skill set. Depending on the method, the learning curve can be quite steep. If you’re just starting out, freezing and dehydrating are the simplest ways to preserve any excess food you may have.

How Much Space Do You Have?

Some crops take significantly more room than others while at the same time producing significantly less food. If your space is limited, every square inch counts. You want the biggest bang for your buck, so consider plants that produce more volume in less space.

The general rule of thumb is about 200 square feet per person for year-round production. Confined spaces often require creative thinking to compensate. Container gardening, vertical gardening, and indoor plants can provide additional spacing when needed.

Seasonal vs Year-Round Crops

Some people only garden during the summer months, opting to take a well-deserved break through the winter. Others look forward to taking advantage of the winter harvest to make up for what they aren’t able to plant during the summer.

Winter gardening allows you to reserve some hardier vegetables for later in the year. However, there are significantly fewer options to choose from since not all plants are resilient enough to withstand cooler temperatures.

In most cases, winter crops are limited to greens and root vegetables. You can always look at the back of your seed packet for optimal planting dates for your specific zone.

For small garden spaces, a winter harvest is an optimal way to produce a little extra food that you don’t have room for in the summer. Conversely, summer gardening means planting all your food at once, which typically requires preservation because it all ripens around the same time.

Know Your Location

What you can grow and when will depend largely on your location, including when your first and last frosts occur, what planting zone you’re in, and what kind and quality of soil you have.

Frost Dates

Timing is everything! Spring planting always revolves around the last frost of winter. Several seeds should be started indoors anywhere from four to eight weeks before that last frost date to maximize your growing season. Likewise, with winter planting, you need to have most of your stuff in the ground before the first frost.

One of the most efficient ways to ensure the best results is keeping a yearly calendar with planting and harvesting dates. It serves as a reminder to make sure you don’t overlook anything. Almanacs are also useful tools to keep you on track with your planting season.

First and Last Frost Dates by ZIP Code | The Old Farmer’s Almanac

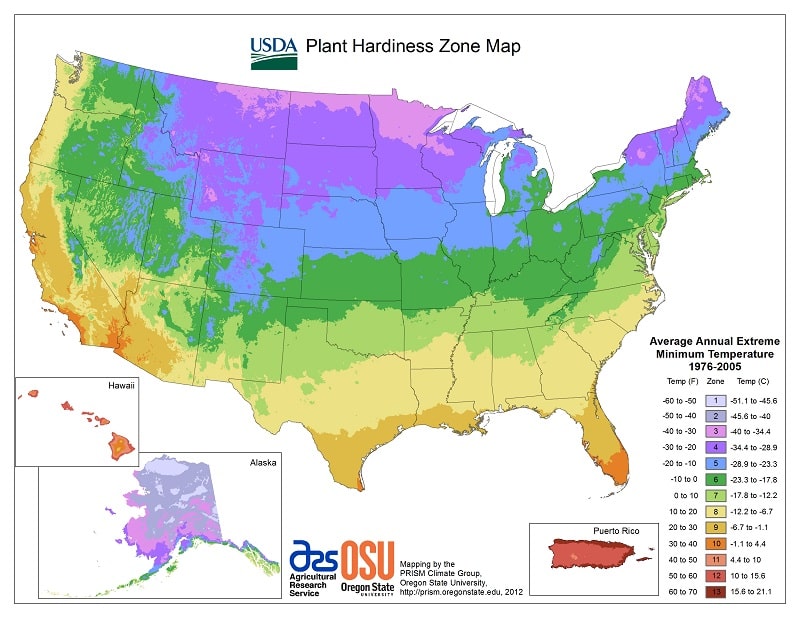

Planting Zone

Location, location, location. Some plants simply don’t grow well in certain regions.

When purchasing seeds from catalog companies, you want to make sure they’re going to grow well in your area. There’s nothing more disheartening than having plants that don’t produce to your expectations because they can’t tolerate your particular climate.

Before you plant anything, make sure they’re hardy enough for your planting zone.

Your Soil

Regardless of your soil type, you need healthy soil for bountiful crops. Not only does it need all the right nutrients, but it also must have the right conditions.

Some plants prefer acidic soils with very specific pH levels while others thrive in sandy, loamy soil. Some plants require nitrogen- or calcium-rich soils.

Getting to know your soil is one of the best things you can do for healthy garden production. Most agricultural extension offices perform soil tests at minimal costs. Otherwise, you can purchase a soil testing kit online or at your local nursery.

Choosing Your Crops

Once you’ve set your goals, it’s time to determine what you will plant. This is largely determined by the goals you set, the amount of space you have, and any food preservation you’re planning.

Think about the foods your family likes to eat in abundance, or think in terms of how much money you can save.

For example, one of my major crops is tomatoes because of their versatility. They take up less space than other vegetables and produce lots of volume. Anything we don’t eat fresh gets canned in the form of tomato sauce or salsa.

Consider Where You Can Save the Most

Vine-ripe tomatoes can go for close to $3/lbs in my area. Not to mention a decent jar of pasta sauce can run anywhere from $5–$8, and a good jar of salsa is anywhere from $3–$6.

Compare that to something like potatoes or corn, which take up a lot of room but don’t produce nearly as much volume. In addition, both are relatively cheap at the grocery store or farmer’s market.

I can get 10 pounds of potatoes that last three to four meals for under $6 and canned or frozen corn at the store for under $1. Growing tomatoes is by far the best bang for your buck.

When to Plant

It’s essential that you plant at the right time—both too early and too late will result in a disappointing or nonexistent harvest.

Once you’ve determined what you will grow, find out when they need to be planted and create a calendar. Life is often busy, and it’s very easy to forget what should be put into the ground from one week to the next. A calendar helps keep you on track.

Additionally, you need to start many seeds indoors before the last frost date. For example, February is the prime time for getting seeds started in my location.

How Much to Plant

You’ve figured out what to plant and when to plant; the next question is how much to plant. To gather realistic calculations, keep track of what vegetables your family eats for at least two weeks, preferably a month. Include all meals with fresh, canned, or frozen vegetables, and don’t forget any snacks consumed throughout the day.

Once you’ve collected your data, multiply it by twelve for an idea of how much your family consumes over the course of a year. If you only have a few weeks of data, adjust your calculations. Multiply one week by 52, two weeks by 26, or three weeks by 18.

For example, we usually eat green beans once a week. If I’m planning to preserve enough to get through the year, then I’d plant enough for 52 meals.

It’s also a good idea to add an additional 15%–20% to your final numbers to compensate for lower-than-expected yields.

Seasonal Calculations

Alternatively, if you’re only eating seasonally with no intention of food preservation, you can calculate your numbers based on the growing season.

For example, bush beans take almost two months to mature and are only harvestable for a few weeks.

When eating seasonally, determine how many meals with bush beans you plan on eating during that two- to three-week period when you’re able to harvest your beans. Then calculate the number of plants needed to supply that many meals.

If you use succession planting, then you can multiply that by how many times you plant. For example, I grow six bush bean plants at the start of the season and add three plants every three weeks thereafter.

Because bush beans have a short harvesting period, staggering the plants through succession ensures my family has beans throughout the entire summer.

Succession Planting

Here’s an example for my family of five. One plant produces approximately two cups of beans. So I usually need 1 ½ plants per meal. This allows for our serving sizes that are generally larger than ½ cup, plus a little extra for a round of seconds for my big eaters.

| Vegetable | Meals per week | Servings | Days to harvest | Plants to start | Succession | Total plants needed | Total meals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bush beans | 1 | 5–6 | 60 | 6 | 3 plants every 3 weeks Feb–Aug [6+(3×9)] | 33 | 11 |

Bear in mind that succession planting requires continually germinating seeds throughout the summer, so there is a bit more work involved. One advantage, however, is using a relatively small amount of space because you’re pulling out old plants as you’re planting new ones.

Here’s a short list of garden plants that work well for succession planting:

- Bush beans

- Carrots

- Cilantro

- Chard

- Dill

- Green onions

- Lettuce

- Radishes

- Spinach

For smaller spaces, it’s a good idea to plant succession crops using plants that have relatively shorter days to harvest.

Doing the Math

Many avid gardeners calculate their average yields based on pounds produced per plant compared to the pounds consumed per week. Likewise, there are plenty of seed companies that produce yield charts for determining the number of plants needed.

This is probably the most common mathematical formula floating around on the internet:

Determine Yield Needed

Vegetables consumed per week (in pounds) x number of weeks needed = total yield needed (in pounds)

Determine Plants Needed

Once you’ve determined how many pounds you need, use that number to determine the number of plants you need.

Yield needed (calculated above) ፥ pounds produced per plant = number of plants needed

You can see this formula worked out in detail in the video above.

Additionally, plenty of charts circulating the internet provide pounds per plant for just about any fruit or vegetable you can imagine. Likewise, many charts simply tell you how many plants you need without giving you any idea how much food comes from those plants.

Furthermore, you have to take all those pounds per plant and translate it into ½ cup serving sizes, which can be like Greek for people who struggle in math. I hardly ever think in terms of pounds, and I rarely, if ever, weigh my produce.

So, for the most part, I find these charts unhelpful, tedious, and time-consuming.

Meals Per Plant

When I plant my garden, I want to know how many meals I can expect from each plant that goes in the ground. Most calculations you find on the internet are based on ½ cup serving sizes. In my experience, this is not a reasonable expectation.

Therefore, over the years, I’ve created my own chart of the most common garden vegetables that make the process much simpler in terms of planting. It’s based on my family of five, which typically consumes ⅔–1 cup of vegetables per serving size.

It should be easy enough to adjust if your family is larger or smaller. Additionally, you’ll still have to gather your data and calculate how much you’re consuming within a 30-day timeframe.

What to Expect From Common Crops

Common Vegetables

| Type | Produces | Days to harvest | Serving size per person | Plants needed for 4–5 people |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bell peppers | 5–10 peppers | 90–100 days | ½–1 pepper | 1–2 meals per plant |

| Bush beans | 20–25 pods, or 2 cups | 50–60 days | ¾–1 cup | 3 plants per meal |

| Corn | 2–4 corn cobs | 60–100 days | 1 cob | 1–2 plants per meal |

| Cucumbers | 10–15 cucumbers | 50–70 days | 1/2–1 cucumber | 3–4 meals per plant |

| English peas | 30–40 pods/plant, or ¼–½ lbs | 60–70 days | ⅔–1 cup | 4–5 plants per meal |

| Heirloom tomatoes | 10–20 tomatoes | 60–80days | 1 tomato | 2–4 meals per plant |

| Hot peppers | 25–30 peppers | 50–90days | 3–5 peppers | 1–3 meals per plant |

| Okra | 20–30 okra | 65 days | 4–5 pods | 1 plant per meal |

| Pole beans | 50–100 pods, or 3–4 cups | 50–60 days | ¾–1 cup | 1 plant per meal |

| Pumpkin | 2–5 pumpkins | 90–100 days | 1 ¾ cup puree | 5 pies per plant |

| Snap or snow peas | 30–40 pods/plant | |||

| ¼ to ½ pound | 60–70 days | 10–20 pods | 3–4 plants per meal | |

| Squash | 5–10 squash | 60 days | ½–1 squash | 1–2 meals per plant |

| Zucchini | 5–10 zucchini | 35–55 days | ½–1 zucchini | 1–2 meals per plant |

Garden Greens

| Type | Produces | Days to harvest | Serving size | Plants needed for 4–5 people |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collards | 1 head | 70–80 days | 1 cup | 1–2 plants per meal |

| Kale | 1 lbs leaves, or 3–6 cups | 25–30 days | 1 cup | 1–2 plants per meal |

| Lettuce | 1 head, or 2–4 cups | 30–70 days | 1 cups | 1 meal per plant |

| Spinach | ¼ lbs leaves, or 1–2 cups | 45–60 days | 1 cup | 4–5 plants per meal |

Root Vegetables

| Type | Produces | Days to harvest | Serving size | Plants needed for 4–5 people |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beets | 1 beet | 45–60 days | 1 beet | 4–5 plants per meal |

| Carrots | 1 carrot (¼ pound) | 60–80 days | 1–2 carrots | 5–10 plants per meal |

| Onions | 1 onion | 100–120 days and 10–14 days to cure | ½–1 cup | 1–2 plants per meal |

| Potatoes | 5–10 potatoes | 100–130 days | 1 potato | 1–2 meals per plant |

| Radishes | 1 radish | 20–30 days | 3–5 radishes | 15 plants per meal |

| Sweet potatoes | 5–10 sweet potatoes | 90–120 days | ½–1 sweet potato | 1–2 meals per plant |

| Turnips | 1 turnip | 40–50 days | ½–1 turnip | 3–5 plants per meal |

Additionally, 1–3 plants of these garden fruits are usually sufficient enough to get my family of five through the summer with a few left over to give away:

- Watermelon

- Honeydew melon

- Cantelope

These vine plants can consume a lot of space, so if you’re limited, stick to one plant.

Furthermore, kitchen herbs not only save lots of money, but they also taste much better than anything you find in the store. One plant is usually sufficient for any of these herbs, and many can even be grown indoors.

Oregano and thyme are best grown in containers since they’re very invasive. Dill and cilantro are great for succession planting, especially if you plan on pickling or canning.

Now is the perfect time to begin many of your seeds indoors. Spring planting flies by, so if you’re thinking about a garden this year, don’t delay, or you’ll miss out!

Just remember, these calculations are based on a family of five. If your family is larger or smaller, don’t forget to adjust the numbers.

If you need additional help designing your garden, check out our permaculture garden and survival garden articles.

[ad_2]

Source link